Introduction

Imagine meeting the person you will become decades from now. What questions would you ask? What advice might they give? Across time and cultures, humans have been fascinated by this encounter with a “future self,” a vision of who we might become, shaped by the choices we make today. This imagined figure has inspired hope, guided ethical behaviour, and motivated people to plan beyond the immediate moment.

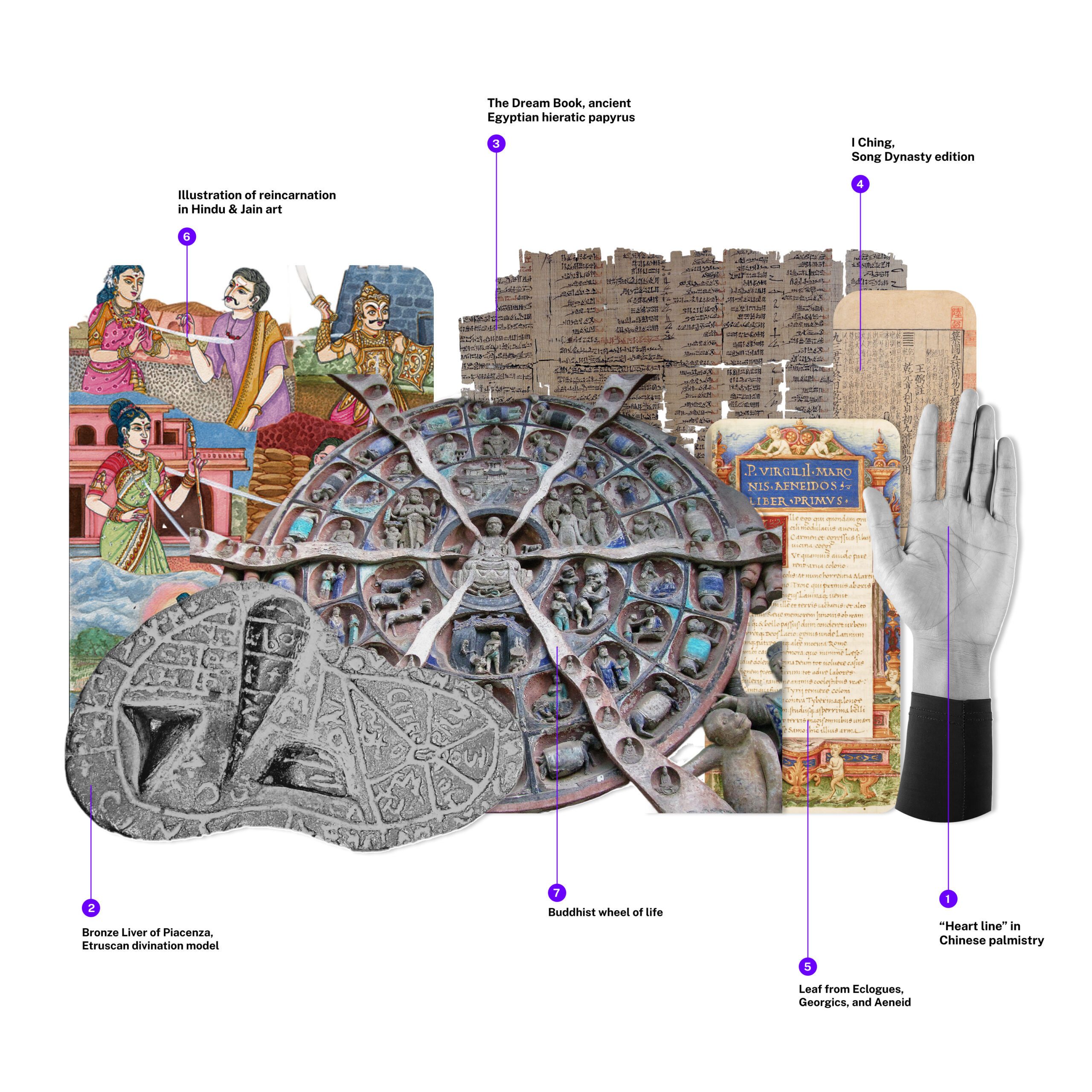

From ancient oracles to modern vision boards, rituals, writing, and imagination have all served as bridges between the present and the future. In ancient Egypt, Rome, and China, divination practices let individuals externalize their future selves through symbols, dreams, or sacred texts. Philosophers and religious traditions, from Stoics and Christians to Buddhists and Hindus, offered frameworks for shaping the self across time, urging reflection, moral growth, and mindfulness of long-term consequences.

Even in the modern era, the dialogue with our future selves continues through journaling, goal-setting, and creative visualization. Writing letters to a future self, imagining best-case scenarios, or planning multi-generational projects are contemporary ways to maintain continuity with what is yet to come. By tracing these practices — ancient and modern, personal and cultural — we can see a universal human impulse: the desire to connect with, guide, and be guided by the self we are destined to become.

Historical and cultural practices

- Photo by Ahmad Roihan Muqoddes, Pexels.

- Bronze liver of Piacenza [Photograph]. Wikipedia.

- The Dream Book [Image]. British Museum.

- I Ching Song Dynasty print [Photograph]. Wikipedia.

- Leaf from Eclogues, Georgics and Aeneid – Walters W40055R – Open Obverse [Manuscript illumination]. Wikipedia.

- Illustration of reincarnation in Hindu & Jain art [Image]. Wikipedia.

- Buddhist Wheel of Life [Photograph]. Wikipedia.

Humans have long sought ways to understand and influence their future selves. Some of the earliest bridges across time were carved into ritual. In ancient India and China, palm readers would trace the faint creases of a person’s hand, treating the “life line” as a map of vitality or the “heart line” as a clue to loves and losses yet to come. In Rome, haruspices (a type of diviner in ancient Rome originally adopted from the Etruscans) unrolled the warm liver of a sacrificed sheep onto a ritual table, convinced that the gods had etched messages into its colour and texture. In Babylon, if someone witnessed a bad omen, from a dog howling at the wrong time to a shadow falling strangely, elaborate namburbi ceremonies were staged to “rewrite” fate through purifying rites, incantations to appeal to the gods, or transferring the bad fate to an object. These rituals made destiny something you could glimpse, and sometimes even negotiate with.

Dreams were another way the future sent messages. In New Kingdom Egypt, the Ramesside Dream Book offered instructions: if you dreamt of your teeth falling out, it warned of misfortune; if you dreamt of drinking beer, good fortune awaited. Northern Europeans scattered rune stones across cloth, interpreting the way a jagged thorn rune or a flowing water rune landed as hints of what tomorrow might hold. In ancient China, the I Ching was consulted by tossing coins or yarrow stalks, with the resulting hexagrams read as guidance for decisions, a blend of chance and reflection not so different from flipping a coin today. Even literature served: in Rome, a reader might open Virgil’s Aeneid at random, letting the first line they saw serve as a prophecy in a practice called sortes.

Beyond divination, philosophy and religion offered structured visions of the future self. Stoic thinkers such as Marcus Aurelius wrote nightly reminders to themselves — almost like pep talks— urging patience with hardship and moral steadiness. In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the future self is imagined in relation to divine judgment and accountability, where each deed in the present shapes the soul’s fate in the world to come. In Hindu and Buddhist traditions, the future self was imagined across cycles of reincarnation: actions now could ripple forward into many lifetimes, making good deeds and mindfulness essential. Daoism taught flowing with the changes of time, while Confucianism cast the self as a work in progress, cultivated through relationships and duty.

Writing has been a particularly enduring bridge to the future. In eleventh-century Japan, Sei Shōnagon’s pillow book recorded lists of hopes, observations, and small pleasures — intimate notes meant as much for her future self as for posterity. Medieval monks in Christian monastic communities in Europe kept conscience journals, cataloguing daily failings and virtues in hopes of improving tomorrow. By the seventeenth century, Samuel Pepys meticulously recorded not only the events of London life but also his spending and habits, creating a mirror for his future self — almost like an early spreadsheet for self-management. Across cultures, such writing turned the present into a message aimed forward in time: “This is who I am today, and who I hope to become.”

Taken together, these practices reveal a shared impulse: to reach forward in time and open a dialogue with our future selves. Whether through entrails, dream books, or diaries, people sought to make the unknown tangible, to give their present actions weight in the eyes of a self they had not yet become.

Modern practices

In contemporary life, the dialogue with our future selves continues through everyday habits and deliberate rituals. One of the most popular is the vision board: a collage of images, words, and symbols representing a desired life. A wall of magazine cut-outs — the dream house, the mountain summit, the word “freedom” in bold — becomes a portrait of the self we hope to inhabit. The act of cutting and arranging is itself a ritual: by making the future visible, we keep it alive in the present. Similarly, people write letters to their future selves, sometimes sealed in envelopes or scheduled through online services to be delivered years later. Teenagers often write about hopes for their twenties, while adults may write to their retired selves. Opening these letters can feel uncanny, as if receiving a message across time from a caring stranger.

Journaling remains another bridge to the future self. Bullet journals, mood trackers, or daily reflections let people monitor habits and chart growth. Looking back at an entry from five years ago can create a shock of recognition: “Was that really me?” Such encounters remind us that we are always in dialogue with the selves we used to be and the selves we are still becoming. Even annual rituals like New Year’s resolutions function as handshakes across time. A list scribbled on 1 January — “run a half marathon, save more, call Mum weekly” — is both a promise and a provocation: will your future self thank you, or shake their head at your forgetfulness?

Modern culture has also revived older ideas under the banner of manifestation and visualisation. Popular books such as The Secret (2006) by Rhonda Byrne encourage readers to vividly picture success, by for example writing affirmations on sticky notes, or mentally rehearsing a promotion or a house purchase, as if feeling the exercise could bring it closer. But unchecked belief in effortless manifestation can backfire as described in the following section.

Some people even flip the perspective, writing not to their future self but from it. One striking example is Bruce Lee’s 1969 “My Definite Chief Aim” letter, in which he declared: “I, Bruce Lee, will be the first highest paid Oriental super star in the United States. In return I will give the most exciting performances and render the best of quality in the capacity of an actor.” At the time, such ambition looked implausible — he was a struggling Asian actor in Hollywood. Yet within a few years he had become a global star. His letter functioned as both prophecy and instruction, keeping him relentless in training and work. It shows the power of a vivid self-portrait to steer daily choices.

Finally, modern practices extend beyond the individual to the collective. The idea of “cathedral thinking” popularised by philosopher Roman Krznaric and inspired by the medieval builders who laid stones for churches they would never see completed, frames long-term projects such as climate action or space exploration. Planting trees whose shade we may never sit under, or designing technologies for future generations, are acts of trust in humanity’s shared future selves. They remind us that the future self is not only private but communal: a figure we co-create, across generations.

Taken together, these practices show that the ancient impulse to converse with the future adapts to new contexts. Whether through collages on a bedroom wall, affirmations whispered in the mirror, or multi-generational projects, people today still seek to make the unknown tangible, to inspire their present actions by imagining who they — and we — might yet become.

The science of future-self thinking

The modern fascination with manifestation and visualisation is best seen as a continuation of age-old practices in a new guise. Exercises such as imagining one’s “best possible self” have been shown to boost optimism, sharpen goals, and sustain motivation. Vividly picturing a hopeful future can improve optimism, emotional regulation and resilience under stress. Neuroscience confirms these benefits: anticipating positive future outcomes activates reward pathways in the brain, releasing dopamine and reinforcing behaviours aligned with long-term goals. Picturing a thriving self navigating future challenges, can also help individuals reinterpret present difficulties as opportunities for growth. This forward-looking perspective helps cultivate adaptive coping strategies. Yet research also cautions against overconfidence: when people believe that success can be “manifested” without effort, they often take riskier financial decisions and suffer costly missteps.

Psychologist Hal Hershfield’s work provides a compelling framework for why the future self matters. His studies show that when people feel a vivid sense of continuity between who they are today and who they will become, they make more prudent, ethical, and farsighted choices. In contrast, those who see their future selves as strangers are more impulsive, more likely to cut moral corners, and less willing to save. Financial behaviour illustrates this vividly: individuals with stronger future-self continuity tend to accumulate greater lifetime wealth. Experiments reinforce the effect: participants who interacted with age-progressed digital avatars of themselves, or who wrote letters to their future selves, consistently favoured larger, delayed rewards over immediate gratification. In other words, making the future self visible helps people act in ways that person will thank them for.

These insights echo what psychologists Hazel Markus and Paula Nurius described in 1986 as Possible Selves Theory, a foundational concept in self and motivation research that continues to be influential today. The idea is that people’s visions of who they might become, both desired and feared, shape present motivation and conduct. Possible selves serve as cognitive bridges, turning abstract hopes into concrete standards for behaviour. A student imagining herself as a future doctor studies harder; an athlete picturing defeat trains with greater discipline to avoid it. The future self operates not just as a fantasy, but as a working guide for present choices.

Even symbolic or legacy-driven behaviours reflect this connection. Passing down family recipes, heirlooms, or stories establishes continuity across generations, linking past, present, and future selves. Research on symbolic immortality suggests that these acts reduce existential anxiety, provide meaning, and enhance well-being. By investing in the future self—personally, financially, and socially—humans navigate life with greater foresight, ethical awareness, and resilience.

Taken together, these findings underscore that the imagined future self is not merely fantasy but a practical tool. Across ethics, decision-making, financial planning, resilience, and legacy, the more vividly we can picture our future selves, the better equipped we are to protect their interests and to live today with purpose.

Going forward

If people across history have always tried to meet their future selves, what does that mean for us today, living in an age of fast change, constant distraction, and growing inequality? In many cultures, the future self wasn’t imagined purely in the mind—it was made tangible through rituals. Ancient people read stars, cast runes, or consulted ancestors; others wrote diaries or letters as a way of speaking to the person they might become. These practices remind us that the future self doesn’t always have to feel like “me.” Sometimes it appears as a stranger, a guide, or even a warning.

There’s also the question of control. We like to think that picturing a successful future self will push us toward better choices, and often it does. But history and psychology both show how often our predictions go wrong. Vision boards, resolutions, and long-term plans can inspire, but they can also set us up for disappointment when life takes unexpected turns. Crises—from pandemics to financial shocks—make it clear that the future is never fully ours to script. Perhaps connecting with our future selves is less about control and more about learning to live with uncertainty.

And, critically, not everyone has the same freedom to imagine far into the future. Language, money, and social circumstances shape whether people can plan decades ahead or whether they must stay focused on surviving today. Future-self thinking, then, can be a privilege. This raises a bigger question: can we create rituals, tools, or collective practices that help more people share in imagining futures so that it’s not only about private goals but about what we build together?

Maybe the real task isn’t to solve the puzzle of the future self once and for all, but to keep the conversation alive. To hold the tension between seeing our future selves as familiar and as strange, between dreaming of control and living with unpredictability, between private ambitions and shared horizons. The future self may never be a fixed figure waiting for us; it might always shift, surprise, and escape us. What matters is finding ways—through ritual, writing, or collective imagination—to keep listening for its voice.