In 2024, we partnered with Kristiania University of Applied Sciences Service Design class and renowned design anthropologist and psychologist Anna Kirah who teaches there.

The class’s ethos closely mirrors our own. Where many design programmes focus on creating polished artefacts, Kirah’s approach foregrounds the lived expertise of those who face the challenges.

She writes,

“Individuals, groups of individuals and even the system transform by fundamentally changing their mindsets,

-

by accepting that people are experts in their own lives, and

- through continuous involvement of all actors within a service in the making of said service.”

This commitment to designing with rather than for made the course a natural collaborator in tackling our deceptively simple brief:

design ways to encourage long-term thinking in financial life.

What we did not anticipate, however, was the level of sophistication, energy, and depth the students brought to this task. Being an undergraduate class, the cohort was young and drew in some external students from other disciplines.

Their methods ranged from immersive interviews to system mapping, and their ability to synthesise theory with lived experience exceeded our expectations. Rather than producing speculative concepts for a grade, they treated the semester as a genuine design laboratory, probing assumptions, questioning norms and even our brief, and proposing interventions that felt not only imaginative but also implementable.

For us, this was as much a lesson in the potential of student-led inquiry as it was a collaboration: a confirmation that fresh, cross-disciplinary perspectives can often cut more sharply into entrenched problems than professional orthodoxies.

The challenge

The surface simplicity of our brief to the students hid a demanding complexity: “Design a way, solution, or concept that activates long-term thinking in people’s financial lives.”

It explicitly rejected the expectation of an app or campaign. Instead, it called for cultural reorientation: away from short-termism and toward financial lives that feel more secure, free, and pleasurable.

This framing was not arbitrary. It draws on earlier research that underpins much of our work, which identified the “financial well-being triad”—security, freedom, and pleasure—as a crucial, human-centred lens for understanding financial well-being. Yet taking the triad seriously complicates the task: each dimension is indispensable, yet none is sufficient on its own. Designing with all three in mind at once requires confronting tensions that most financial products or policies sidestep.

The students were asked to lean into this complexity, working with four principles: an outside-in ethos (designing with people and for people), future orientation (not constrained by today’s rules), transdisciplinarity, and openness (sharing results with the public and relevant institutions).

The brief was less a design exercise than an invitation into a systemic problem space: how might we reshape not only financial practices, but also the values, relationships, and institutions that underpin them?

The process and ethos

The course did not unfold as a theoretical exercise. Students committed many hours to reading, mapping, interviewing, and prototyping. They tested methods, set aside those that yielded little insight, and pivoted toward richer approaches when early survey results proved too superficial.

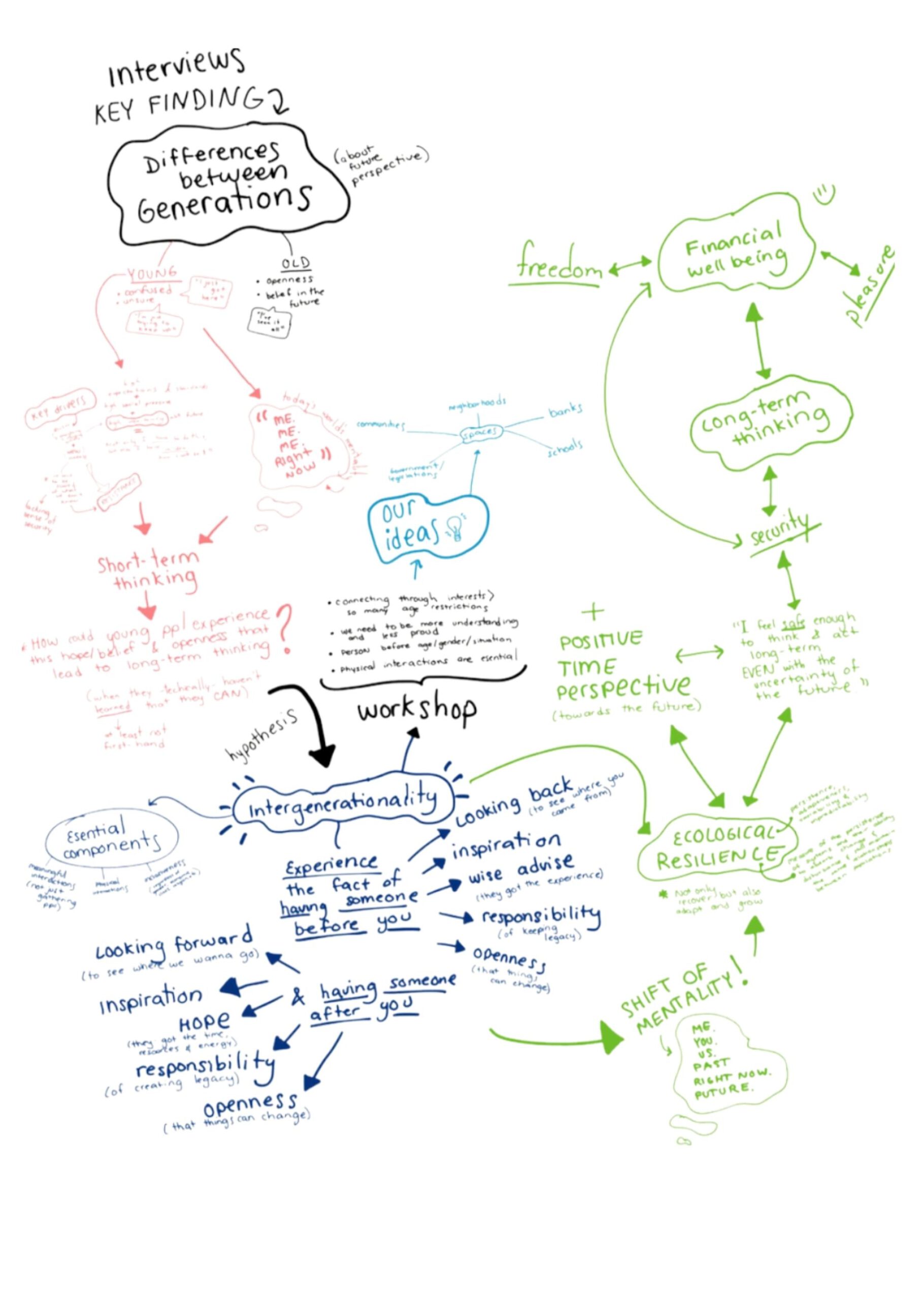

They built gigamaps—large, layered diagrams of systemic interconnections—as tools for analysing complexity and guiding decisions. They carried out interviews and held workshops to debate values with teenagers, probe assumptions with small business owners, and listen carefully. They confronted the limits of surveys, iteratively rebuilt their interview guides, and learned to hold contradictory evidence without rushing for closure.

From this sustained engagement, students worked in groups of four to five, to produce three distinct project outcomes: a child-first prototype to reward nonmaterial choices, a trust blueprint packaged for implementation, and a scalable intergenerational service framework. Each stands on its own, but together they form a triad of complementary outcomes any lab, bank, school, or city could pick up tomorrow.

Direction 1:

Next Step — Rewarding nonmaterial choices in childhood

One team began with a critique of materialism: the cultural tide of privileging objects over experiences, relationships, or resilience. Their interviews underscored its consequences—impulsive spending, stress, reduced savings—and highlighted asymmetries of power. “Today, companies hold the power, and they’re not going to make changes on their own,” one interviewee remarked. Another worried that “people aren’t prepared for unforeseen situations.”

Rather than try to change adult habits retroactively, the team pivoted upstream: childhood. They reframed the question plainly: “How can one design a system for children that rewards selfless actions and nonmaterialistic behaviours?”

Their answer is Next Step, a concept and prototype that turns prosocial actions into the “reward,” not consumption. Behaviours like repairing, sharing, and helping are noticed and celebrated. Practised early, these habits become reflexes later. The prototype is not marketing collateral but a working design skeleton: structure maps, low-fidelity tests, and high-fidelity screens.

Schools and youth programmes might trial Next Step as a bridge between classroom and home, with simple routines like two prosocial “quests” per week. Families could reflect on what earned recognition. Museums, libraries, and after-school clubs might host repair days where children record “learning-by-fixing” as achievements. Banks with youth accounts could experiment with a “prosocial bonus,” matching small savings deposits with community-oriented tasks.

The credibility of Next Step lies in its research depth. The team logged 72 articles, four films, four books, and six podcasts on the mechanisms of “retail therapy” and resilience. When surveys disappointed, they pivoted to long-form interviews and co-creation workshops with 13- and 14-year-olds. The move toward childhood values was not a hunch but an evidence-driven decision.

Direction 2:

Social Currency — Rebuilding trust through language and relationships

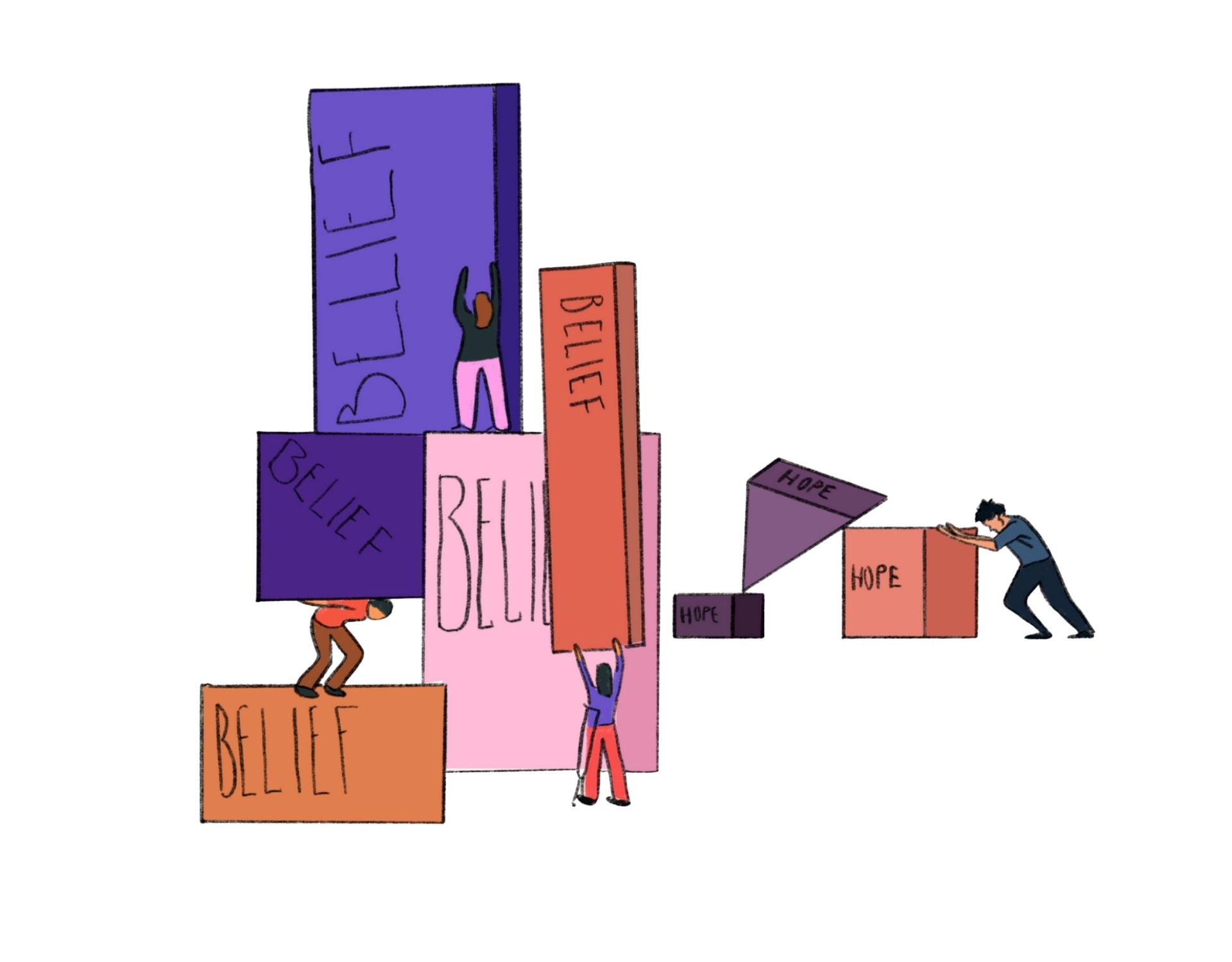

Another team’s maps of financial life kept converging on one connector: trust. Trust in institutions. Trust in information. Trust in the future. They worked with 18–30 year-olds, conducting open-ended interviews rather than box-ticking surveys. Their findings were stark: “Living together in a society is only possible when the primal instinct of trust is given.” Another interviewee said, “Because of fluctuation in the economy, I don’t trust banks in the country I live in.” And again: “We need action over empty promises to be able to trust.”

From workshops, the team derived human-centred principles: Putting people over numbers; Building trust through transparency and honesty; Building trust through understanding and clarity in banking. These were not slogans but operational commitments.

Their concept, Social Currency, packages these insights into scenarios, implementation outlines, and five “conversation starters.” It focuses on the ordinary but decisive moments where trust is built or broken: onboarding, problem resolution, pricing pages, collection calls, follow-up emails.

A bank might use the insights from Social Currency to redesign the first week of account onboarding end-to-end, replacing jargon with first-person language. Pricing and fee rationales could be published in a single phone-readable page. Frontline staff could use “conversation starters” to navigate difficult calls without defensiveness.

The team did not claim that language alone could rebuild trust. They treated words as the surface of deeper commitments: honesty in pricing, visibility in decision-making, relational banking in a digital age. Social Currency translates diffuse mistrust into actionable steps.

Direction 3:

Intergenerational Futures — Pairing guidance with reassurance

The third team framed their work as a “practical utopia.” Their hypothesis: stronger ties across generations foster a mindset of legacy and continuity, making long-term thinking feel natural. Their literature review drew from psychologist Philip Zimbardo on time perspective, philosopher Roman Krznaric on deep-time humility, and Matthew Wizinsky on designing after capitalism. But the urgency came from their own words: “We have to act now and inspire humankind to think long-term, creating a resilient mindset that looks beyond immediate rewards.”

Street interviews revealed subtle dynamics. Informants often answered questions without being asked, showing the value of listening rather than prompting. The team’s challenge became: “How might we create an intergenerational support network that provides guidance, reassurance, and promotes shared learning, to encourage long-term thinking across different life stages?”

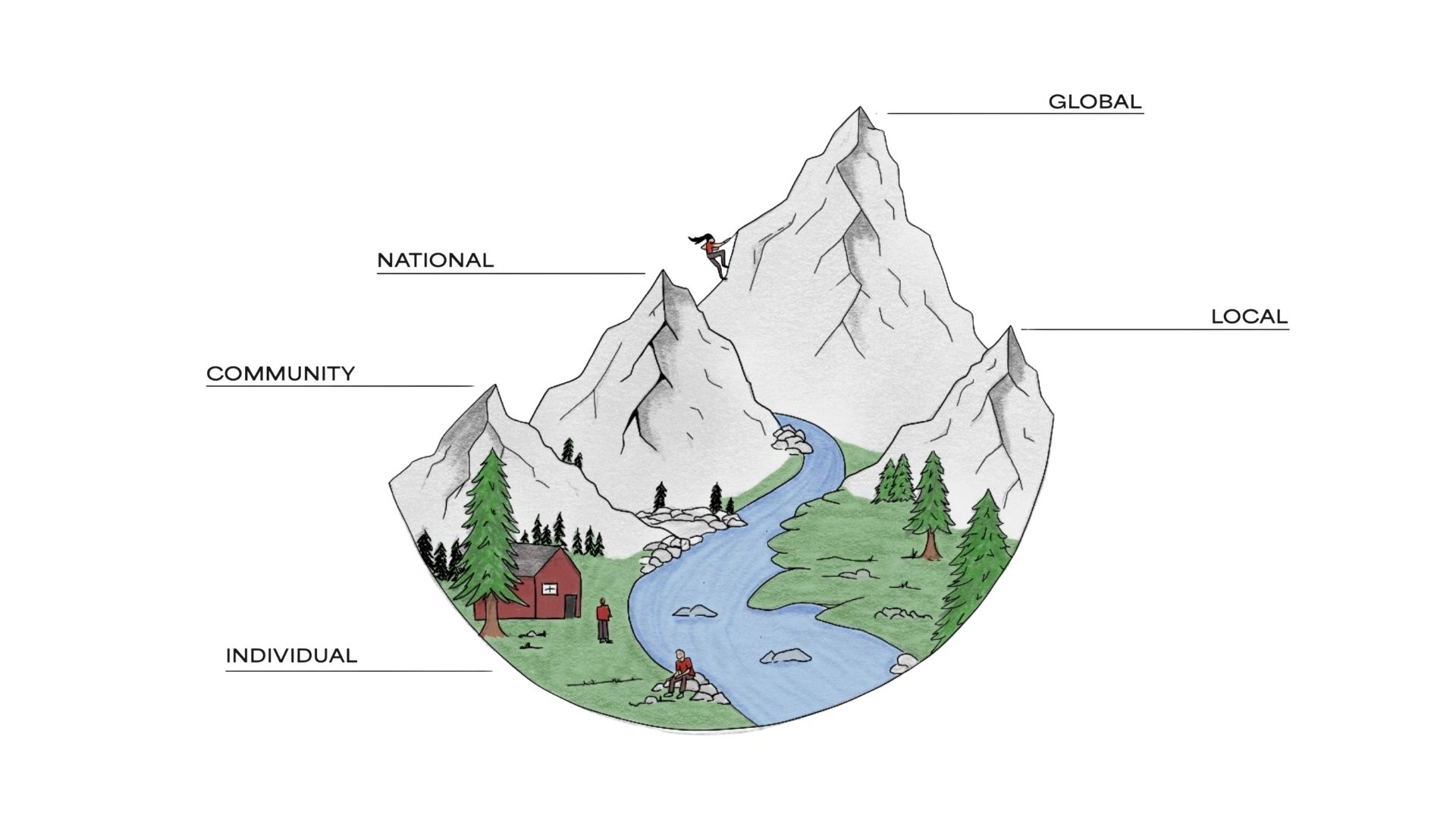

The resulting framework, Intergenerational Futures, is a service architecture, not a single app. It defines intergenerationality, sets design considerations and limits, and suggests levels of operation: from light-touch mentoring and co-learning circles to deeper co-living pilots. It is scaffolding for schools, libraries, banks, or neighbourhood organisations.

Inspired by Intergenerational Futures, a library could host a weekly “Financial Life Studio” pairing retirees with school leavers. A city agency might create an “advice-for-time” exchange where older adults offer guidance on housing bureaucracy in return for digital help. Banks could develop “banking neighbours”—trained volunteers who translate products into life events. The metric is not downloads or likes, but whether reassurance and guidance expand people’s willingness to plan beyond the immediate.

Why the outcomes matter beyond a classroom

The outcomes align with wider evidence: people prefer peace of mind to complexity, real assets to speculative products, clarity to jargon. They add cultural depth by focusing not just on what people buy or save, but on how they imagine futures together. Each outcome carries a theory of change:

- Next Step:

strengthen nonmaterial values early to avoid unlearning short-termism later.

- Social Currency:

design for trust by putting people over numbers and let metrics follow.

- Intergenerational Futures:

embed guidance and reassurance across life stages, making futures a conversation, not a burden.

These are not competing bets but mutually reinforcing. A bank that pilots Social Currency can also sponsor Next Step in schools and host intergenerational circles in branches. A city that fosters intergenerational mentoring can reward prosocial youth acts with experiences rather than things. A school that runs Next Step can invite grandparents into project days. The connective tissue is cultural: design with people, for the long term.

What to carry forward

The class took three pathways to answer our brief: one for children, one for institutions, one for communities. They produced prototypes, frameworks, and scenarios. They also left something quieter: beginnings that others can pick up, measure, and adapt. In a world that often rewards promises over progress, their work invites a different posture: listen, make something usable, measure change, share learning, repeat.

If financial life is to feel more human, it will not be through perfect products but through relationships of trust built across generations. As Anna Kirah has written, “Throw away your ego and grab on to copious quantities of humility.” That humility—toward children’s values, toward young adults’ mistrust, toward elders’ guidance—is the foundation of designing financial futures that endure.

Cover photo: Vonecia Carswell, Unsplash